Over the past two days, the Centre for Asian Legal Studies (CALS) and the International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES) organised a Conference on Religion and Constitutional Practices in Asia. Religion is a highly salient feature of many Asian societies and its significance extends beyond the private sphere. In countries like Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia, religion was a key factor in driving nationalist and anti-colonial consciousness, and it remains a key tool for social and political mobilization. In other countries, religion is intimately tied with ethnic identities, and in some, the salience of religion found its way into constitutional texts and arrangements. There is thus great diversity in how religion manifests itself in the social, political, and legal (constitutional) settings of these Asian countries. The Conference explores the interaction between religion and constitutional law in Asia, especially in those countries where strong religious identification exists in the social and political spheres. Featuring scholars from South Asia, South-East Asia, Australasia, and North America, the conference will assess trends and developments in thirteen Asian jurisdictions.

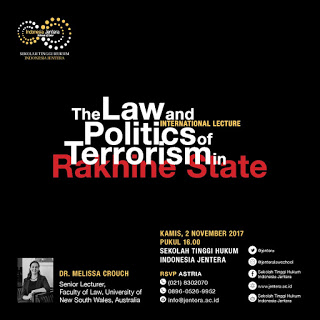

Seminar at Jentera Law School

On 2 November 2017 I visited Jentera Law School, a new law school that began in 2014 based in Jakarta, Indonesia. Jentera Law School has a young and vibrant faculty with strong connections to key law reform and policy institutes, including the Centre for the Study of Law and Policy (PSHK), Hukumonline, and the Daniel S Lev law library. While visiting there, I gave a seminar on the Law and Politics of Terrorism in Rakhine State.

Religious Deference and the Blasphemy Law in Indonesia

It is a delight to be a University of Indonesia Visiting Fellow this month. On 1-2 November, I will give a paper at a workshop on “Law and Governance in Global Context” at the Law Faculty. My paper is on “The Courts, Religious Deference and the Blasphemy Law in Indonesia”

Abstract: The recent criminal trial of Governor of Jakarta, Ahok, has highlighted the controversy over the Blasphemy Law in Indonesia. This raises questions about legal culture, how and why law is used, and the rule of law in Indonesia. My presentation examines the role of fatwa issued against so-called ‘deviant’ religious believers convicted on charges of blasphemy. This is an issue of growing concern in Indonesia, where an increasing number of individuals have been convicted for the offence of blasphemy since 1998. It identifies that fatwa, despite its lack of legal status, may play an influential part in the legal process. A fatwa may be used as a justification or basis for allegations of blasphemy to be lodged with the police. Once a blasphemy case reaches the District Court, a fatwa may also be used as evidence in court to support the prosecutor’s argument that a person is guilty of ‘insulting a religion’. This raises the issue of how the legal system reconciles state criminal law with Islamic fatwa. I examine how Islamic opinions are given weight in court, despite the fact that a fatwa is not recognised as an official or legally binding source of law by the state in Indonesia. Drawing on illustrations from several cases of blasphemy, I argue that a practise of “religious deference” has emerged, where the District Courts defer to the opinion of Islamic religious leaders and fatwa on issues of religious sensitivity. This principle of religious deference is one means by which the secular state courts negotiate and reconcile the demands of legal pluralism.

Seminar: The Struggle for Constitutional Rights and Accountability in Asia

On 12 October I will be giving a seminar at Windsor Faculty of Law, Ontario, Canada. My paper is on: “The Struggle for Constitutional Rights and Accountability in Asia.

“Abstract: The courts are often a key site of the struggle for rights and administrative accountability. In this article, I highlight an important yet understudied avenue for both the historical and contemporary study of comparative administrative law: the constitutional writs. I demonstrate that the constitutional writs are an example of a British colonial legal transplant that originated from the common law and then took on a new life in constitutions across former British colonies from the 1940s to 1980s, particularly across South Asia, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, as well as parts of Africa, the Pacific and the Caribbean. I illustrate the history and development of this model, transforming from the common law remedies of England to a significant constitutional means of reviewing administrative decisions. I offer a comparative view of the politics of administrative law in Myanmar, illustrated by a within country comparison. The study of the constitutional writs demonstrates the interconnection of constitutional and administrative law, and the symbolic nature of administrative review. I argue that the field of comparative administrative law needs to reconsider the history of transnational borrowing and innovation in former British colonies, and go beyond a statutory focus on administrative law to account for the constitutional entrenchment of administrative remedies.

Implementing New Constitutions Workshop

From 13-14 October 2017, Chicago Law School will be holding a workshop on ‘From Parchment to Practise: Implementing New Constitutions’. I will be presenting a paper on “Vehicle for Democratic Transition or Authoritarian Straightjacket? Constitutional Regression and Risks in the Struggle to Change Myanmar’s Constitution“.

The abstract of my paper is as follows: How hard is it to change a constitution that was drafted by an authoritarian regime to legitimate a new political order? What strategies might democratic actors adopt to change such a constitution, and what risks may they face? Democratic actors in Myanmar who seek to change the 2008 Constitution currently face these dilemmas. In the first part of my chapter I introduce the contours and practice of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution in order to demonstrate the new political order that was set in place by the former military regime. I then explore the different strategies that have been used to change the 2008 Constitution – formal constitutional amendment proposals in 2013-2015; informal constitutional change through judicial interpretation in the Constitutional Tribunal; and informal constitutional change in the form of the legislative innovation of the Office of the State Counsellor. These strategies may come with particular risks. I identify the various risks democratic actors have suffered for these attempts at constitutional reform. In particular, I highlight the ways in which constitutional regression has occurred, such as the undemocratic proposals put to a vote in parliament as part of the formal constitutional amendment process. I conclude by considering the broader implications for the study of risk-taking and constitutional change in transitional regimes.

The broader program is available here ‘From Parchment to Practise’.

- Session I: The First Period Problem and a Classic Case

- Welcome

- Tom Ginsburg and Aziz Huq, The Theory and Practice of Constitutional Implementation

- Commentator: Rosalind Dixon, University of New South Wales

- Sandy Levinson, Texas, The First Period Problem in the United States

- Commentator: Eric Slauter, University of Chicago American Studies

- Session I: The First Period Problem and a Classic Case

- Saturday, October 14, 2017

- 8:30am – 9:00am

- Continental Breakfast

Call for panels on Asian Law for the Asian Studies Association of Australia

The Asian Studies Association of Australia will hold its next bi-annual conference at the University of Sydney from 3-5 July 2018. We would like to invite submissions of abstracts for law-related panels around the following themes:

1. Courts and Legal Culture in Asia

2. Legal Pluralism and Human Rights in Asia

3. Public Law in Asia

If you would like to be considered for one of these panels, please contact Melissa Crouch or Simon Butt by no later than 15 October. If accepted, you will then need to submit your paper abstract and register by 1 November 2017.

If you prefer to submit your own panel or individual paper, please see the conference website for further instructions

Arson, exclusion and exodus

ANU Seminar on Rakhine State

Tuesday 3 October 2017

Location: Lecture Theatre 1.02, Sir Roland Wilson Building, ANU

Myanmar has made global headlines in recent weeks due to the flight of almost half a million self-identifying Rohingya to Bangladesh and other neighbouring countries. The exodus follows attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) against Myanmar police outposts in October 2016 and again on August 25 2017 which were coordinated with the release of a report on conditions in Rakhine State by former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan. Massive reprisals by Myanmar Armed Forces and vigilante groups have followed, with refugees describing arson attacks, massacres in villages and wide scale human rights abuses. For decades Rakhine State has experienced recurrent outbreaks of violence. This panel discussion will bring together academic and policy experts to situate the latest events in the history of violence and consider implications for the lives of Rohingya people, for human security of all populations in Rakhine State and for Myanmar’s political transition. Speakers will also present their views on potential solutions – national, regional and global. The speakers include

- Dr Melissa Crouch (Senior Lecturer, University of New South Wales Law School)

- Dr Nich Farrelly (Associate Dean, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University)

- Marc Purcell (CEO, Australian Council for International Development)

- Dr Andrew Selth (Adjunct Associate Professor, Griffith Asia Institute)

- Dr Than Tun (Fellow, Australian National University)

The Convenience of Terrorism in Myanmar

This article first appeared in Lowy’s Institute The Interpreter, 12 September 2017.

The major and protracted humanitarian crisis in Myanmar’s northern Rakhine State has serious local, regional and global implications. Many have rightly deplored the human rights situation and called for urgent humanitarian assistance while the world has become preoccupied with the silence of Aung San Suu Kyi and her fall from grace.

What appears to have gone largely unquestioned, however, is that the military and the government now ascribe the causes of the current conflict to ‘terrorism’. This convenient explanation should not be accepted at face value.

After a series of coordinated attacks against police on 25 August, the government’s Anti-Terrorism Committee declared the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) to be a terrorist organisation.

While this is the first time a group has been declared a terrorist organisation under the nation’s new Anti-Terrorism Law, branding an armed group as ‘terrorist’ appears to be a new trend in Myanmar. On 20 November 2016, the Northern Alliance – a coalition supported by the Kachin, Talaung, Arakan and Kokang ethnic armed groups – began planned attacks on military and police in northern Shan State. In response, on 3 December, the Defence Minister raised a call to brand the Northern Alliance as a ‘terrorist organisation’ in the lower house of national parliament. The same proposal was then raised in the Shan State Hluttaw by the military members of parliament and the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) where it succeeded, 61 votes to 45.

This declaration of the Northern Alliance as a terrorist organisation was highly controversial. This is not only because it was initiated at the state level, but also because in the past these groups have simply been referred to in Myanmar as ‘ethnic armed groups’.

Now the terrorist label is also being applied to the ARSA. This is despite the fact that some of ARSA’s tactics are not necessarily different from those used previously by either the military or other armed ethnic groups.

The declaration of ARSA as a terrorist organisation will have far-reaching consequences, some of which will likely result from major deficiencies in the Anti-Terrorism Law itself. For this is a classic example of a ‘model’ law gone very wrong. While some of the provisions are translations from a global model, many recommended safeguards are absent in Myanmar.

The Anti-Terrorism Committee is headed by the Minister of Home Affairs, who in Myanmar is chosen by the military. The Committee’s mandate is broad. There are no requirements to be a member of the Committee, nor any limit on how many members the Committee can have.

The term of office of the members of the Committee is unspecified. The extent, or more importantly the limits, of their powers are unknown. It remains unclear what investigative or evidential basis is needed to justify declaring a group to be a terrorist organisation.

Worryingly, Anti-Terrorism Committee members or members of the public stand to gain financial rewards if they ‘dob in’ a terrorist. There are also blanket immunity clauses for the military and for Committee members. Committee members cannot be prosecuted for any wrongdoing.

Given that some offences under the Anti-Terrorism Law attract the death penalty, there is much at stake.

In addition to declaring the ARSA a terrorist group, the military and police now appear to be targeting specific individuals under the Anti-Terrorism Law. These tactics mirror the use of the infamous section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law, used to imprison many journalists and activists. The use of section 66(d) has attracted international condemnation; so too should the Anti-Terrorism Law.

For example, on 1 September, Shwe Maung, a former prominent Rohingya politician for Buthidaung Township (in northern Rakhine State) was charged by police under the Anti-Terrorism Law. His alleged crime is that his Facebook page contains some videos that relate to the ARSA and comments that are perceived to show support for ARSA actions.

Shwe Maung is no stranger to the obsessive and irrational persecution that plagues the Rohingya. He is an example of the falling out between the USDP (backed by the military) and elite Rohingya in northern Rakhine State.

In the 2010 elections, three Rohingya, including Shwe Maung, were elected to constituencies in northern Rakhine State. Over their five years in office, they were hounded and bullied out of national parliament.

In particular, they were extensively and intrusively questioned about their citizenship status. The situation deteriorated to such an extent that Shwe Maung fled to the United States. The police may now seek to extradite him back to Myanmar to face alleged terrorist charges.

This is the toxic and twisted politics of terrorism in Myanmar. It helps to explain the stepped-up persecution of an ethnic group which has forced more than 290,000 people to flee to Bangladesh and constitutes a larger displacement crisis than occurred in 1978, 1991 or 2012.

In Myanmar, where the military has perfected the art of terrorising people over decades, the threats come from many sides.

In recent years, for example, the vitriol of Buddhist nationalist groups has added to the anti-Muslim narrative. However, it doesn’t serve the purposes of the security forces to label radical Buddhists, the military or police as terrorists in Myanmar.

Graduation Ceremony for Legal Training Program

On 29 August 2017, UNSW Law hosted the graduation ceremony in Yangon for 36 lawyers who completed the UNSW/ADB Professional Legal Education in Commercial and Corporate Law Training Program.

The training program was designed and run by a team at UNSW Law led by Dr Melissa Crouch.

The intensive training course ran from April to July 2017 and included training on professional legal conduct, contract law, company law, joint ventures, mergers & acquisitions, and environmental law. Participants had to attend all training sessions and pass several written assignments.

The training was conducted in partnership with several prominent law firms in Myanmar, including Baker McKenzie, Allen & Gledhill, DFDL, and Stephenson Harwood. The training benefited from the expertise of Melinda Tun, Khin Thandar, Helen Rhind-Hufnagel, Robin Scott, Min Naing Oo, Jo Daniels and Nishant Choudhry. The program is designed to support the emerging commercial legal profession in Myanmar. The graduation ceremony featured on MiTV (Myanmar television) available here.

Book Review: Buddhism, Politics and the Limits of Law

In recent decades, high profile controversies of monks involved in law and politics, as well as serious violent conflict, across South and Southeast Asia has exposed our current knowledge of the causes and consequences as insufficient. This has generated renewed scholarly interest in the study of Buddhism, law and politics. Benjamin Schonthal’s book on Buddhism, Politics and the Limits of Law is part of this exciting and timely new generation of scholarly engagement on Buddhism and law in Asia. As a leading scholar in the field, Schonthal’s work demonstrates and cements his position as a pioneer in the contemporary study of Buddhism and law. His book joins a small but growing body of literature exemplified in works such as the edited volume Buddhism and Law,[1] the special journal issue of Buddhism and Law in Asia[2] (of which Schonthal is the co-editor), and Walton’s Buddhism, Politics and Political Thought in Myanmar.[3] In addition, Schonthal is on the editorial board of a new journal, Buddhism, Law and Society, that was launched in 2016 and is set to be the latest forum for this growing body of research. In short, Schonthal’s work represents a new turn in the study of contemporary Buddhism and comparative law, and marks the consolidation of this area of study.In Buddhism, Politics and the Limits of Law, Schonthal offers a rich, empirical analysis of a timely and sensitive issue across Asia – the interaction between constitutional law and Buddhism. His book exhibits exemplary socio-legal research, and this quality has been previously recognized as his thesis (upon which the book is based) received the Law & Society Association Dissertation Prize (2013). His book is written in a compelling and accessible style, beginning with an opening story that raises the anomaly of monks (emblematic of religion and the private sphere) in court (symbolic of the public sphere). This visual conundrum of who should stand up to honor whom in a courtroom – religious monks or the secular judge – is powerful and pulls the reader into this intriguing dilemma.Methodologically, Schonthal builds upon the idea of microhistory, and expands on this to develop the concept of constitutional microhistory[4] (illustrated well in chapter 6). This approach enables Schonthal to justify and advocate for the use of sources and materials beyond normative sources of constitutional law.The animating idea central to Schonthal’s work is the concept of pyrrhic constitutionalism.[5] As comparative constitutional law scholars should note, Schonthal is careful to explain that by ‘constitutionalism’ he is referring to a narrow understanding of “practices of drafting and adjudicating constitutional law”, rather than the wider use of government limited by law.[6] His idea then of pyrrhic constitutionalism is one in which the practice of constitutional law may upset the intended aims of the law, including its broader influence on social life…. Anyone interested in how constitutions manage religion should read this book. In addition, scholars who find themselves surrounded by an unwavering faith in the constitution will have their assumptions about the inherent goodness of constitutional law shaken. This arguments in this book have long-lasting and broad implications for the way in which we think and study about law and religion. Schonthal book not only has resonance for contemporary debates in other Buddhist majority countries that constitutionally recognize Buddhism, such as Myanmar and Thailand, but also for debates over the relationship between religion and constitutional law more broadly.

For the full book review – see Melissa Crouch (2017) Buddhism, Politics and the Limits of Law, Asian Journal of Law and Society.

References

French, Rebecca and Mark Nathan (2015) Buddhism and Law: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Schonthal, Benjamin and Tom Ginsburg (2016) ‘Buddhism and Law in Asia’, special issue, Asian Journal of Law and Society.

Walton, Matthew (2016) Buddhism, Politics and Political Thought in Myanmar. Cambridge University Press.

Notes

[1] French, Rebecca and Mark Nathan (2015) Buddhism and Law: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

[2] Schonthal, Benjamin and Tom Ginsburg (2016) ‘Buddhism and Law in Asia’, special issue, Asian Journal of Law and Society.

[3] Walton, Matthew (2016) Buddhism, Politics and Political Thought in Myanmar. Cambridge University Press.

[4] Schonthal, p 18.

[5] Schonthal, pp 11- 17.

[6] Schonthal, p 12.

[7] Schonthal, p 153.

[8] Schonthal, p 7.