At the start of a New Year, its always useful to look back to see where we have been and where we have directed our efforts. I have been fortunate to be involved in various initiatives in Myanmar over the past few years, but particularly while I was at National University of Singapore (2012-2014). Here is a recap on events

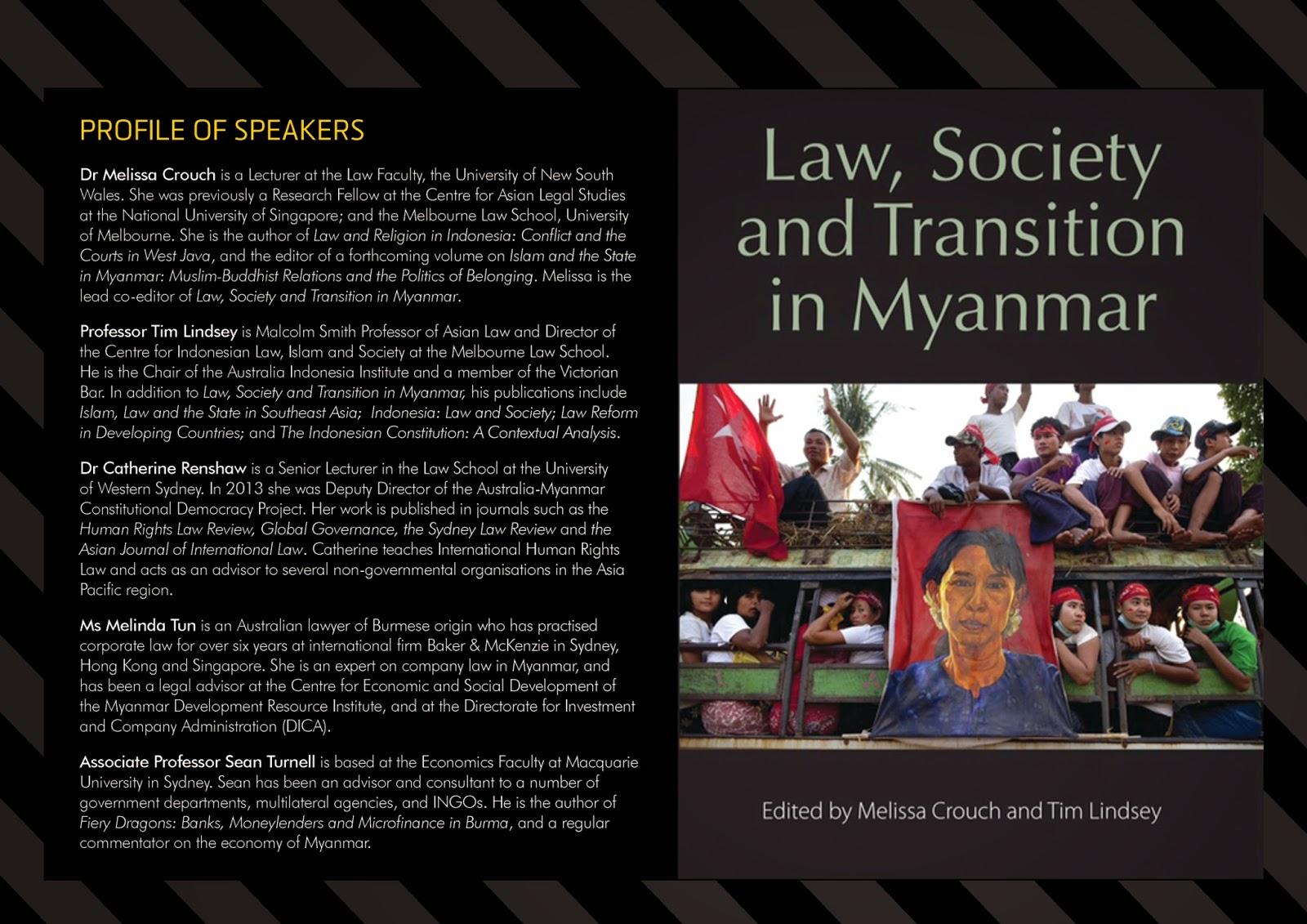

October 2012: Workshop on Directions and Determinants in Law Reform in Myanmar – held at NUS, organised by Professor Andrew Harding. Harding has summarised the discussions from this workshop in a chapter Law, Society and Transition in Myanmar.

Semester 1, 2012:Asian Legal Studies Colloquium (2012), I contributed to two ofProf Andrew Harding’s classes on the legal system of Myanmar.

April 2013: Roundtable on Human Rights and Responsible Business in Myanmar, I gave an update on the legal system at a roundtable organised by Melbourne Law School.

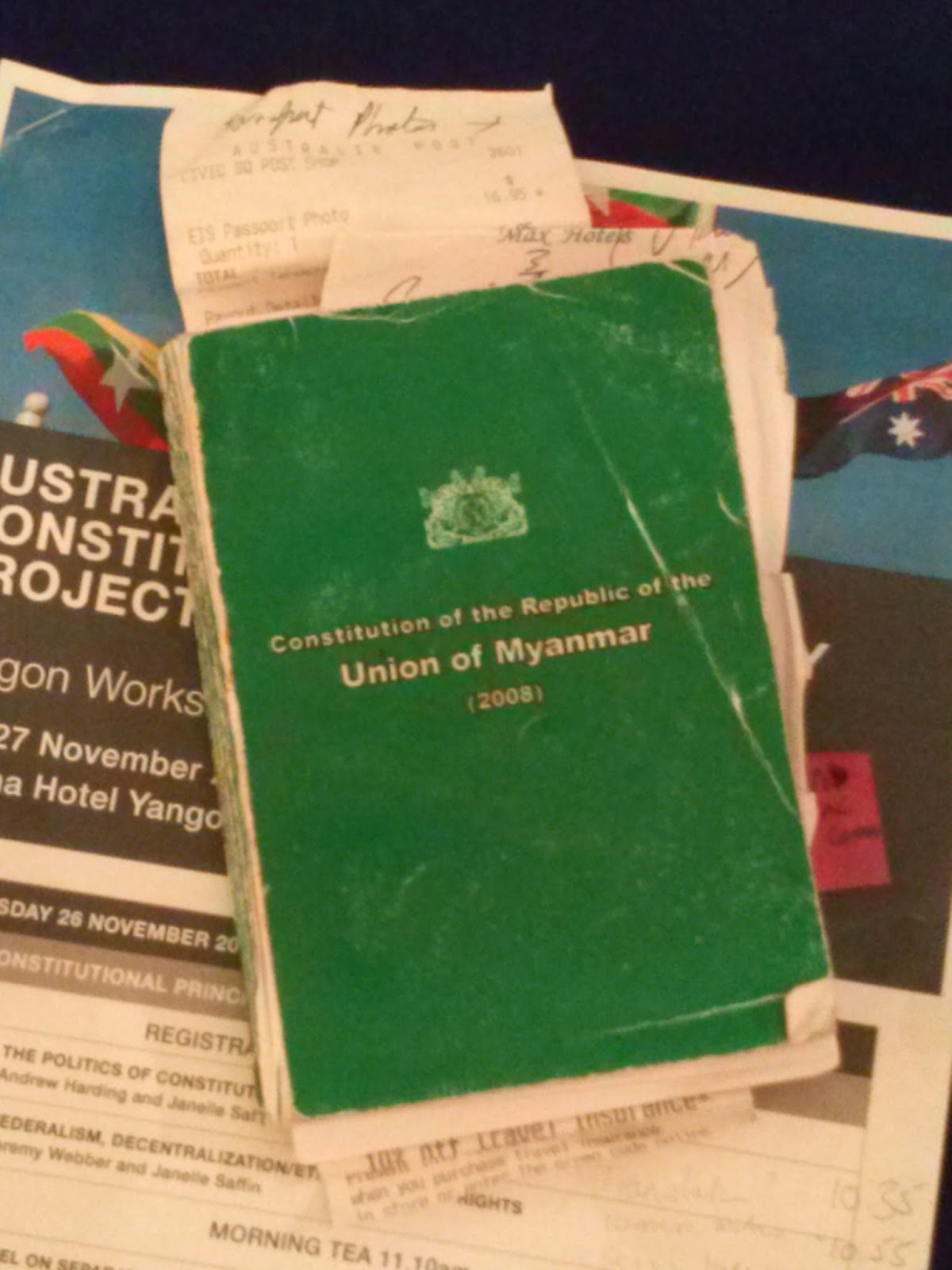

May 2013:Australia-Myanmar Constitutional Law Workshop, – I gave a talk on emergency powers and the relationship between the military and the Constitution. The workshop was facilitated by the Sydney Law School in Yangon.

May 2013: Training Assessment Workshop for the Union Attorney General’s Office, Naypyidaw. This was a preliminary workshop with a range of donors, law schools and law officers from the AG’s office about the future training needs of the Attorney General’s Office. Dr Melissa Crouch attended on behalf of CALS.

June 2013:Annual ATLAS Agora June 2013, Prof Andrew Harding and I gave a seminar on legal reform in Myanmar held at the Law Faculty, NUS.

August 2013: Ministry of Law (Singapore) delegation to University of Yangon and Mandalay University Law Departments. I represented NUS on this trip. The focus was on legal education and possible future cooperation between NUS and the two Law Departments in Myanmar. [MOUs were signed in early 2014]

October 2013: Seminar on ‘Prospects and Challenges for Constitutional Reform in Myanmar’, which I gave at the Asian Law Centre, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne.

October 2013: Rule of Law in Asia LLM course: I taught in the Masters course at the Melbourne Law School, the University of Melbourne. The class was on ‘The Rule of Law in Myanmar’.

January – April 2014 (sem 2): Transition and the Rule of Law in Myanmar elective, I taught anew elective course for LLB/LLM/PhD students at the Law Faculty, NUS.

January 2014:Workshop on Islam, Law and the State in Myanmar, which I organised. The edited volume Islam and the State in Myanmar: Muslim-Buddhist Relations and the Politics of Belonging is forthcoming.

February 2014:Workshop on Constitutionalism and Law Reform in Myanmar, was held at NUS, organised by Professor Andrew Harding, which I also assisted with. I gave a talk on The Constitutional Writs in Myanmar.

April 2014: Seminar at UNSW: I gave a talk on Constitutionalism in Transition: The Writs as a Litmus Test for Law Reform in Myanmar, at the Law Faculty, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

June 2014: Workshop on Legal Education with Myanmar Japan Legal Resource Centre and the University of Yangon, Yangon. I attended on behalf of National University of Singapore.

July 2014: Law Department Review as part of the Social Science Curriculum Working Group Meeting, hosted by the Open Society Foundation, the University of Yangon and Mandalay University, Yangon.

1-3 August 2014: Bi-annual Burma Studies Group Conference: This was an inter-disciplinary academic event organised in collaboration with the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, the Lee Kwan Yew School of Public Policy, and the Law Faculty, the National University of Singapore. The panel I organised was on Religion, Identity and Politics in Myanmar.

August 2014:USAID/Promoting the Rule of Law Project – I participated in a project on Administrative Justice in Myanmar. This including giving a lecture at Mandalay University Law Department.

October 2014:Parliamentary Resource Centre, Naypyidaw: I gave a talk on Administrative Law at the National Democratic Institute in Naypyidaw to Members of Parliament. I also gave a talk in Yangon to lawyers and civil society.

November 2014: Australia-Myanmar Constitutional Democracy Workshop. I contributed to a panel on The Rule of Law, focusing specifically on the issues for the rule of law that are raised in a state of emergency.

It has been a dynamic and fascinating experience. Now I have moved to UNSW, I am becoming involved in initiatives here. I’ll post more on these soon.